Contents

- 1 When should your hard drive be replaced

- 1.1 When SMART reports issues with the drive

- 1.2 If the drive starts making unusual sounds

- 1.3 If the drive becomes slow

- 1.4 Once the drive reaches its designed lifetime

- 1.5 When the drive’s technology becomes obsolete

- 1.6 When the drive’s capacity is no longer sufficient

- 1.7 When getting a new computer

- 1.8 When the drive has completely failed

For the vast majority of data-hoarders, hard drives are their preferred storage medium. As you might expect, it’s not unusual for someone dedicated to the data-hoarding hobby to have several hard drives in use at any one time. The question that we see asked over and over again is “when should I replace my hard drive?“. Whilst there are always different opinions on when a hard drive needs to be replaced, there’s one golden rule that always needs to be followed. You should immediately replace your hard drive when it begins showing any sign of failure. Yes, you might be able to get by for days, weeks, or even months with a hard drive that’s beginning to fail but it really isn’t worth the risk.

With the golden rule in mind, this post will cover the most common scenarios that data-hoarders often face that indicate a drive replacement is on the cards.

When should your hard drive be replaced

When SMART reports issues with the drive

For many years, there wasn’t any reliable way to predict when and how your hard drive would fail. For many users and system administrators, they only first discovered there was an issue with their drive when it was too late, and the drive was about to die or was already dead. Not only was this an inconvenience but it was also quite wasteful. Because it was so difficult to predict a drive’s impending failure, businesses and other organizations often put policies in place to replace all hard drives after a fixed period of time. For example, they might have decided that all hard drives were to be replaced when reaching two years old. As you can imagine, this resulted in drives being replaced that may well have had years of life left in them.

To address this problem, in the mid-1990s a consortium of computer and hard drive manufacturers released a standard known as SMART (“Self-Monitoring, Analysis, and Reporting Technology”). This SMART technology provides a mechanism for hard drives to report their health back to the computer which can then, in turn, warn the system’s user of an issue.

There are various characteristics of the disk that SMART is able to monitor, and these vary by hard drive manufacturer. If you’re interested in the low-level detail, the SMART Wikipedia article is excellent. In short, however, if you receive a SMART warning (usually at boot-time, from BIOS/UEFI), it’s strongly advised that the drive be replaced.

It’s worth mentioning that SMART isn’t completely foolproof. It’s entirely possible that your hard drive can fail unexpectedly without generating a SMART warning. In fact, it was found in one study that this happens 36% of the time. Even with SMART enabled, it’s essential that you have a robust backup strategy in place.

If the drive starts making unusual sounds

In the same way that your car might start making strange noises before it breaks down, unusual sounds from your hard drive should also worry you. Even when SMART monitoring is active on a hard drive, it’s not uncommon for audible anomalies to preclude other warnings. A hard drive is a mechanical component after all so it can sometimes soldier on for days or weeks with a sticking bearing, or a catching platter, before it either stops working or SMART picks up on the issue and notifies the user.

If you notice your drive suddenly begins to sound different, it’s best to replace it ASAP. If the hard drive forms part of a redundant system (e.g. RAID), then just swap the drive out and dispose of the old one. If it isn’t redundant, then you’ll have to plan to replace it and double-check that your backups are valid.

If the drive becomes slow

It’s quite natural for a hard drive to become a little slower over time as more and more free space is consumed. This is usually due to fragmentation as isn’t a great cause for concern. That’s not what I’m talking about here though. If you notice that your drive is taking considerably longer to read or write data, then it may well be a sign that it’s beginning to fail. If for example, you try to open a small file and you can hear your hard drive repeatedly clicking away for thirty seconds or more, then you should perhaps start to worry.

Sometimes, the operating system will get tired of waiting for the drive to complete its task and will give up, presenting an I/O error message to the user. Again, this should at the very least prompt you to investigate your drive’s health status.

If you have SMART monitoring enabled on the drive, hopefully, it will alert you to whatever issue is causing these slowdowns before things turn fatal for the drive.

Once the drive reaches its designed lifetime

Like almost all items produced today, hard drives have an expected lifetime. Nothing lasts forever and any decent hard drive manufacturer will perform tests on their products and publish an estimate of how long you can expect them to last.

A number of years ago, the metric used to determine how long a hard drive should last was “MTBF”, or Mean Time Between Failure. Simply put, the “MTBF” was the average time you could expect to use a hard drive, under normal conditions before it failed. Of course, there’s really no such thing as “normal conditions”, you may consider normal use to be twice a week for an hour, I might consider normal use to be 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

Fortunately, there are now more accurate ways of estimating a hard drive’s usable life. In recent years, most manufacturers seem to have settled on a measure known as the “Load/Unload Cycle”. The “Load/Unload Cycle” is a count of the number of times the hard drive’s actuator arm (the arm to which the drive’s read/write head is mounted) has been parked or unparked. Without going into too much detail, this measure is more representative of how much mechanical strain the drive has been under.

If you download the datasheet for your hard drive, or lookup its specifications online, you’ll easily be able to find the designed “Load/Unload Cycles” target figure, often under the “Reliability” section of the document. Even the cheapest consumer-grade desktop hard drives are rated to at least 300,000 cycles nowadays. To check the current number of cycles your drive has performed, it’s just a case of reading this value from the drive’s SMART data. You can use something like PowerShell or CrystalDiskInfo under Windows, or smartctl under Linux. The “Load/Unload Cycle” count is stored as SMART attribute 193 (or “C1” in hexadecimal).

If you discover that your drive is nearing, or has exceeded the designed number of cycles, it might be wise to think about replacing it sooner rather than later.

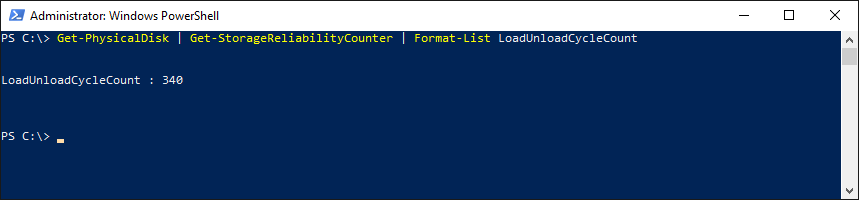

By way of example, I checked the current “Load/Unload Cycle” count on one of my hard drives that’s around 6 months old. It’s rated for 300,000 cycles and as you can see from the image below, it’s currently sitting at only 340.

The PowerShell command used, for reference, was “Get-PhysicalDisk | Get-StorageReliabilityCounter | Format-List LoadUnloadCycleCount”

When the drive’s technology becomes obsolete

Sometimes, a hard drive can be performing fine, as it was designed, yet it has slowly become obsolete. This usually happens when a new and improved technology comes along and over the course of months or years, the cost of this new technology plummets. For example, a few years ago, I had a number of older PC systems still booting from traditional mechanical hard drives. These hard drives were working fine and had varying capacities of between 250GB – 500GB. At the time, SSDs (solid-state drives) had been around for a few years and their prices had really begun to fall.

I checked the price of comparable SSDs (with capacities of 240GB – 480GB) and was pleasantly surprised. At the time, I was able to pick up a 240GB SSD for around £25 (35 USD), or a 480GB SSD for a mere £40 (55 USD). I decided, at that point, it no longer made sense for me to be running these older/legacy hard drives, even though on paper they were functioning perfectly. Replacing them with new SSDs would mean a massive performance increase whilst also giving me some peace of mind due to their improved reliability.

If your hard drive is very old, it may be worth pricing up a replacement and looking into whether the newer technologies would provide some benefit. You’ll probably discover that replacing a very old/obsolete drive today is more practical than simply waiting for it to fail.

When the drive’s capacity is no longer sufficient

It’s no secret that storage requirements are increasing all the time. Generally, with each year that passes, the data we’d like to save consumes more space than it used to. For example, photos and videos are higher-definition than they used to be, software applications are much larger than in the past, and even our computer’s operating system itself needs more storage space as its features evolve.

In addition to this, our data accumulates. Even if you’re not yet a data-hoarder, you’re probably reluctant to delete last year’s holiday photos just so you have enough free space to save this year’s snaps.

Even if your old hard drive is still going strong, many years after you bought it, there comes a time when it’s just no longer large enough. Deleting old files and performing housekeeping eventually reaches a point of diminishing returns and it just makes sense to replace your hard drive with a larger model.

In a similar vein, perhaps over the years you’ve bought additional storage devices (external drives, USB flash drives, etc) and are fed up with juggling them all. If you have three 1TB hard drives and a few USB sticks, you can make your life easier by just buying a 4TB or 8TB drive and consolidating everything.

If your system already has several hard drives installed or attached over USB, there’s also an environmental benefit. Rather than powering multiple hard drives, you can migrate all your data onto a single new hard drive. Not only will you be saving electricity by only powering one drive, but that one drive is probably more energy efficient than any one of your older hard drives.

When getting a new computer

Getting a new computer often provides a good opportunity to have a look at the data you’re holding and to review your storage needs. It’s tempting to either just copy the entire contents of your old hard drive to your new one or even to remove your old hard drive and install it in your new computer. This generally isn’t a good idea, and it’s better to have a “spring clean” and perform some basic housekeeping.

Before even buying a new system, have a look at your current system and see if there is anything that can be safely deleted. Of course, it usually goes against the data-hoarding principles to delete data but even so, certain things are fair game. For example, temporary files can go to start with. Duplicated data is also a waste of space. If you have zipped and un-zipped copies of the same downloads, for example, clean these up.

Once, you’ve had a clean-up, work out how much space you currently need and compare that to the current hard drive capacities on the market. A rule of thumb I used to use (before I became a full-blown data-hoarder), was to buy double the amount of storage I needed at that point in time. For example, if my old computer held 2TB of data, I made sure the hard drive in my new system was at least 4TB.

When the drive has completely failed

This is really the worst-case scenario and a position you don’t want to find yourself in. Sadly, however, many people only even consider replacing their hard drive once it has completely failed. It’s too easy to ignore the warning signs of a failing hard drive, and even easier to ignore the fact that your hard drive is getting old, especially if it’s still plodding on.

If your hard drive is aging, or showing signs of wear and tear then do yourself a favor and just replace it today. If for financial, or other reasons, you’re not able to replace your hard drive, at least make sure you have a decent backup of your data in place, and budget for a replacement drive accordingly.